Behind Guantanamo's walls, there are more walls

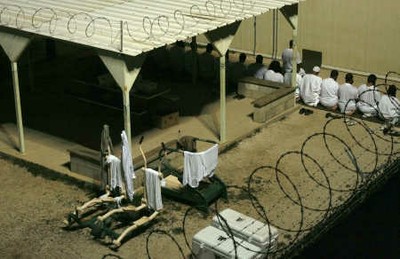

The bright lights of the prison yard in Guantanamo’s “lenient, minimum security” Camp 4 belie the fact that it is 5:15 a.m. Here, inmates kneel for morning prayers. The inmates hang their laundry from exercise equipment in the foreground. Photo credit: Chris Zuppa, St. Petersburg Times.

St. Petersburg Times

by Meg Laughlin

July 5, 2009

GUANTANAMO BAY NAVAL BASE, Cuba. The doctor in charge of the Guantanamo prison hospital says he's "extremely proud" to be there, but he won't give his name. A pale man with auburn hair in his 50s, he tells us he's an internist from Jacksonville and to call him "Smo" — for senior medical officer. The head nurse says to call her "Audi" — like the car. Forgive them if they gush, they say, as we walk through the shiny hospital, but they are "bowled over" by the quality of care for the prison's 240 detainees. The hospital is a regular stop on the media tour of Guantanamo, which, the military has gone to great lengths to convince the world, is operating in a "safe, humane, legal and transparent" manner despite previous stories. But seeing patients is impossible, Smo tells us, even with their permission in hand. Instead we're led through the empty X-ray room and the endoscopy lab, while a noise machine gurgles loudly in the background. Audi tells the four reporters on the media tour that the noise machine helps sick inmates rest. FBI reports, available to anyone with an Internet connection, say it was once used for sensory deprivation during interrogations. We ask about the rail-thin Yemeni detainee, 31, whose death was widely reported the week before. Didn't he die in the hospital? "Can't talk about it because it's under investigation," Smo says. We ask about the daily forced-feeding of a few dozen hunger strikers who are protesting years in isolation. Three former detainees have told me the procedure is "sadistic" because of the restraint chair and how the tube is jammed in and jerked out.

Smo objects to that characterization, preferring to describe the sessions as "endearing" because detainees report "their brothers who are starving themselves to help each other."

He directs us to a display: cans of strawberry, butter pecan and chocolate Ensure next to 4 feet of yellow rubber tubing, which, we are told, is "gently inserted" from nose to stomach. The "delicious flavors" are to entice them to eat, we're told.

"They taste it when they burp," Audi says, smiling.

We ask to see the 12-strap restraint chairs that hold hunger strikers immobile for hours while the Ensure is pumped in.

"Off limits," Audi says.

But rest assured, she says, the feeding is a "social hour" that detainees enjoy.

"In fact," says Smo, "some detainees do it after eating their meals just to be part of the good experience."

• • •

Before I went to Guantanamo in June, I called National Guard Brig. Gen. Greg Zanetti, who had been deputy commander in 2008, to get an idea of what to expect. He told me staff "will open the whole kimono and show you everything."

But what we saw and heard during our 30-hour tour over two days was set-up displays and cheerful staff speeches. Maybe Guantanamo has become the "caring old folks home for terrorists" that Zanetti described to me. But, since we weren't allowed to find out for ourselves, it was impossible to know.

What we do know is that government reports say that hundreds of people from around the world were tortured there between 2002 and 2004, and hundreds are held still in numbing isolation without being charged. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates recently declared the Guantanamo prison "tainted" and supports President Barack Obama's plan to close it.

Since early January 2002, when a few dozen detainees were herded off planes in shackles, earphones and goggles, about 780 men have come through Guantanamo. Of those, about 540 have been released and returned to their families, though the Pentagon reports a few named detainees have joined al-Qaida.

Among the detainees who remain at Guantanamo are dozens who have been declared harmless and cleared, and about a dozen "high-value detainees" like Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the admitted mastermind of the Sept. 11 attacks.

But, regardless of their status, we were not allowed near any of the detainees, having to settle for a carefully scripted tour that seemed to stubbornly ignore facts openly available to the world outside.

• • •

Most of the detainees eat food prepared in a sparkling kitchen by smiling head chef Sam Scott, a civilian who wears a bonnet with a bow. Nearby, assistants pull trays of baklava, oatmeal raisin cookies, and brownies from the oven and shape tortilla bowls — which may account for some of the 6,500 calories a day that the prison's Web site says detainees are fed.

Scott entreats us to taste samples of the day's dinner and guides us to several Styrofoam containers on display: chicken breasts in a delicious, spicy broth with cumin, garlic and red bell pepper, served with pasta, olive oil and black olives. There is also fried fish and butter-garlic noodles. There are versions of both entrees with no seasoning.

It's hard to square this elaborate display of gourmet food with former detainees' description of their food as "very bland."

"Every detainee chooses every meal," Scott says.

Where are the menu cards they check off?

"Not available."

Nearby dollies are stacked with large coolers full of meals.

Can we open them?

"Not allowed."

But it would make the display so much more believable, we say.

Scott opens a cooler, pulls out a Styrofoam container and flips the lid. It's the bland meal.

Could we now see a spicy meal?

"No more," says Scott, as she leads us out.

• • •

Camp X-Ray, now deserted, was the first prison camp opened at Guantanamo in January 2002.

The 320 open-air cages are overgrown with bug-infested vines and tall grass. On this rainy day in June some cages are flooded and swarms of mosquitoes hang in the air. Hutia, rodents the size of cocker spaniels, climb on the mesh.

The media handlers proudly point out a pipe vacuum system for waste. But government documents show it was not working when the camp was open and each prisoner was given a bucket, which often overflowed.

Camp X-Ray is infamous for the prisoners' exposure to the elements and the interrogations that took place there. According to a 2008 Department of Justice report, interrogation techniques used on detainees — many of whom have since been released — included the following:

Hands and feet shackled together so closely they couldn't stand, sit or lie down comfortably for days; exposure to extreme heat and cold; being forced to wear leashes and perform dog tricks with women's underwear on their heads; sleep deprivation for days with rock music, strobe lights, gurgling noise machines and ice-water dousing; bending thumbs back, wrapping heads in duct tape, slamming prisoners into walls and punching them to the ground.

One of our media handlers tells us that none of this can be called "torture" because it wasn't defined as torture at the time.

"Besides, we're doing a great job now," says Sgt. Emily Greene.

• • •

When X-Ray closed in late spring 2002, prisoners were moved to buildings on the other side of the base. Then, as the population dwindled, they were concentrated into a smaller area, and, according to Zanetti, the former deputy commander, treated increasingly better.

By January 2008, when Zanetti was there, detainees who weren't designated as "maximum-security prisoners" were coming up with trivial complaints that showed how spoiled they were.

To make his point, Zanetti read to me from a daily briefing from the first week of April 2008: "Prisoner 765 wants onions and parsley on his salad; 845 wants a better detainee newsletter; 632 wants a Bowflex machine to build his abs."

But, according to the master list of prisoner names and numbers provided by the Pentagon, prisoners 632 and 845 left Guantanamo in 2006, two years before the complaints, and the number 765 was never assigned to a prisoner. I left Zanetti several phone messages seeking clarification, but he hasn't called back.

By our June media tour, Camps 1, 2 and 3, where most prisoners went when X-Ray was closed, were practically deserted, and most of the prisoners lived in Camps 4, 5 and 6 on the south side of the naval base.

Guards call Camp 4 "lenient, minimum security" because prisoners share sleeping space and an outside area of scabrous soil surrounded by high fences with razor wire, covered with opaque green cloth so they can't see out.

On display in a concrete day room is the animated film Madagascar, about a lion, a zebra and a giraffe who escape from a zoo, only to find life on the outside fraught with problems. Checkers, backgammon and library books like The Helen Keller Story are also on display, along with flip-flops, a bendable toothbrush and earplugs. The Web site touts 13,000 books but we only see a few dozen in the library.

When we say we have permission to talk to some Camp 4 detainees, a guard tells us we're not allowed near them because of the Geneva Conventions.

"It protects their privacy and dignity," he tells us.

He shows us the shuttered windows of the concrete building where they are held.

"They do that so you media people can't see in," he says.

Camp 5 is called "maximum security" because prisoners spend 22 hours a day locked in cells with constant bright lights. The time outside of their cells is spent alone in a 20-by-10-foot concrete cage.

"They can kick their water bottle like a soccer ball," a guard says.

When we ask the head psychologist, who calls himself "Eldorado" after the car, about the effects of prolonged solitary confinement, he says: "You see a lot of depression and anxiety."

But Smo interrupts: "There is no solitary confinement here. They just spend a lot of time alone in their cells."

To make the point that the detainees want nothing to do with us, the head guard at Camp 5 takes us to a window where he opens a blind so we can see a detainee sitting about 25 feet away. The inmate immediately ties a black plastic bag to a fence to block our view.

"You see how they don't want the media looking at them?" he says.

But we realize we are looking at a latrine and we have been invited to watch them defecate.

Camp 6 is called "ultralite maximum security" by the guards. There's an area with steel tables and stools under a big TV encased in Plexiglas. Among the personal possessions on display: small packets of olive oil and Emile Zola's novel Joie de Vivre, about a French family finding small pleasures in hard times.

Once again, we mention having permission to talk to a few of the prisoners.

"It's not up to them or their attorneys because they're enemy combatants without status," says the head guard.

So, it's not the Geneva Conventions?

"Not always," he says.

• • •

Cpt. Dan Bauer greets us in a concrete block room of wooden desks and leather chairs where a panel decides the status of detainees — whether they're still enemy combatants, no longer enemy combatants or never were enemy combatants.

Bounties of about $5,000 per person, totaling millions of dollars, were paid in Pakistan and Afghanistan to deliver innocent people to Guantanamo, according to statements made by former Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf and accounts in the New York Times. Once captured, prisoners were tortured to confess and to name others. "Serial snitches" at Guantanamo get all kinds of perks — from freshly made hot tea to Subway sandwiches to chess sets.

Knowing that, we ask Bauer how the panel decides what information is reliable.

Bauer begins slowly: "It's part of our job to sift through information … "

But before he can finish his sentence our media handler jumps to her feet and says, "Time's up."

Can't we hear his response?

"Sorry, no," she says.

The media handlers are mostly soldiers in their 20s and 30s from the Florida National Guard. Most give the expected spin, but a few quietly say off the record that it troubles them to constantly set up a wall so we don't know what's going on.

Later, watching the news in the military chow hall, we learn that an island in the South Pacific has agreed to take more than a dozen detainees, but no one tells us that 10 detainees are being flown out that very day. It's impossible to tell whether the secrecy is deliberate on the part of our media handlers or if the information is also being kept from them.

• • •

We end our tour of Guantanamo in the office of Col. Bruce Vargo, the Army commander over the prison.

Wouldn't fewer displays and canned responses, and more real life situations make the tour more credible?

"That's a valid point," Vargo says. "A lot of people are working on issues that have to do with transparency, the Geneva Conventions and habeas corpus, and we expect improvements."

But the only improvements we can see is new construction, not more openness.

We ask Vargo: Why so much new construction when the prison is scheduled to close in seven months?

"If it's six months or one month with improvements, it's the right thing to do," he says, "and we always try to do the right thing."