Attorney-client meeting room was bugged, Navy lawyer testifies at Guantánamo

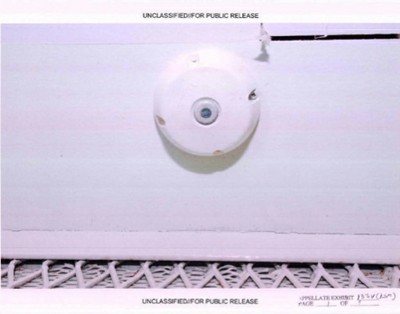

Pentagon-released photograph of the Louroe AP-4 audio surveillance unit found

in the rooms where Guantanamo prisoners undergoing trials by military commis-

sions met with their attorneys (Photo credit: Miami Herald).

Miami Herald

by Carol Rosenberg

February 12, 2013

The military had a hidden microphone in a room where defense attorneys met detainees awaiting death-penalty trials, a senior prison official disclosed at the war court Tuesday.

But, eavesdropping equipment aside, nobody was using it to listen in on the confidential conversations prisoners have with their lawyers or the Red Cross, Navy Capt. Thomas Welsh, the prison camps’ chief staff attorney testified.

Welsh said he discovered the eavesdropping capability in January 2012, after eight months on the job at Guantánamo, by spotting a “law enforcement official” listening in on a meeting between a detainee, prosecutor and defense lawyers. They were discussing a possible plea deal inside Camp Echo, a compound of huts. The microphone was inside a device that looked like a smoke detector.Welsh was called to testify by defense attorneys in the 9/11 trial hearings who are trying to uncover what intelligence agencies, if any, are capable of listening in on their confidential meetings, either at the court or the prison camps as they prepare to defend alleged mastermind Khalid Sheik Mohammed and four others accused of orchestrating the Sept 11, 2001, terror attacks.

Welsh is a career Navy attorney bound by the same ethics practices as civilian lawyers. He said he was so struck by the discovery of the capability eight months into his job as prison camps lawyer that he sought out the chief of the guard force, Army Col. Donnie Thomas, to gain assurances that nobody at Guantánamo was turning on the microphones to listen in on privileged attorney-client meetings.

The judge, Army Col. James Pohl, enabled the defense investigation last month after a hidden-hand censor, listening in on a secret channel, reached into Pohl’s court, and clicked off the audio feed to the public.

Defense attorneys then discovered the dummy smoke detector in their meeting rooms. “It looks like a smoke detector,” Welsh agreed under questioning by Mohammed’s attorney, David Nevin. “I agree with your point it was not recognizable, was not readily identifiable” as a listening device.

Neither Welsh nor Thomas apparently bothered to notify their boss, however, about the eavesdropping capability.

On March 6, 2012, the prison camps commander, Navy Rear Adm. David Woods, wrote Southern Command that at the place where lawyers meet accused in his prison camps “no microphones are installed to ensure privacy between the attorney and client is maintained.”

Defense lawyers got the email from Welsh, moments before he testified Tuesday, as part of a discovery order issued by the judge.

The lawyer said he found it in a search of his own email in-box but had never read his boss’ email to higher headquarters in Miami because he wasn’t asked to approve it in advance.

The issue of whether attorney-client confidences have been breached has overwhelmed these latest Sept. 11 pretrial proceedings. Defense lawyers spent much of the morning questioning the courtroom’s director of technology, Maurice Elkins, about who gets to listen to unfiltered feeds from the state-of-the-art $12 million courtroom.

The courtroom was designed specifically to thwart outside eavesdropping, and was brought in specially by barge several years ago for the 9/11 trial. It has 32 microphones arrayed inside capable of capturing eight different channels of sound, Elkins said, that are piped to a court reporter, recorders and unidentified intelligence agencies through a classified system.

Defense lawyers made clear in questioning that they were not informed in a briefing on the courthouse on the eve of the May 5, 21012, arraignment that outside intelligence agencies were listening in on the court through a special surround-sound-style feed — live and amplified, not on the public’s 40-second delay.

Defense lawyers say they got repeated assurances since taking up these death-penalty cases that their attorney-client privilege was being honored, that nobody was listening in on their conversations. The chief prosecutor, Army Brig. Gen. Mark Martins reiterated it on Sunday night in a statement to the press and in court filings.