Free and Uneasy. Tale of 5 Muslims: Out of Guantanamo and Into Limbo Cleared by U.S. of Terror Ties, They Won’t Return Home Due to Fear of Punishment. China Demands Repatriation

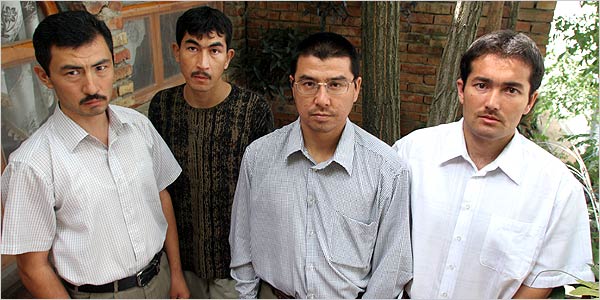

Four of five former Guantánamo prisoners, including Abu Bakker Qassim,

third from the left, outside a refugee center in Tirana, Albania.

By Andrew Higgins

June 2, 2006; Page A1

TIRANA, Albania -- After four years in Guantanamo Bay, Abu Bakker Qassim, a former terror suspect cleared last year of having ties to al Qaeda, got word last month that he finally would be set free. He and four fellow Muslims from China were loaded onto a U.S. military transport plane in the middle of the night, shackled to the floor and flown for 12 hours to their new home: a converted military barracks in Tirana, the capital of Albania. The compound is located on a potholed road strewn with garbage. It has high walls, bars on the windows and a guard at the gate. The five men occasionally leave but don’t venture far. They’ve found no one in this small Balkan country who knows their native language, a Turkic tongue spoken by the Uighur (pronounced WEE-gur) people of China. “I think Allah must be testing our patience,” says Mr. Qassim, a 37-year-old father of three from Xinjiang, a historically Muslim region of deserts and mountains in western China. Pointing to strands of rusty barbed wire outside his window, he rolls his eyes. Freedom, he says, “is not what we expected.” The U.S. is also in a predicament it never expected: What should it do with Guantanamo inmates who have been found deserving of release but who face jail or execution if returned to their homelands? It’s a question that has grown urgent in recent weeks as the United Nations and even stalwart ally Britain have turned up the heat on Washington over Guantanamo prison. Critics say the camp stains America’s reputation, upends the Geneva Convention governing treatment of prisoners and fuels Muslim anger. Eighty-nine inmates are now staging a hunger strike, drawing further attention to their plight. Washington’s hesitation to repatriate some detainees reflects its growing unease with authoritarian states it initially enlisted as partners in the post-9/11 war on terror. U.S. forces used an air base in Uzbekistan during the war in Afghanistan, but Washington strongly criticized the former Soviet republic last year when Uzbek security forces killed scores of unarmed protesters. Uzbekistan then evicted the U.S. military. Fear of being sent home is so strong that an exonerated Egyptian detainee, Ala Abdel Maqsud Muhammad Salim, had his U.S. lawyers ask a federal court in January to block his release to avoid his being sent to Egypt, where he expected harm. The U.S. dropped a plan to return the sickly and nearly blind prisoner. He’s still in Guantanamo. U.S. officials say they scouted for two years for a country ready to take Mr. Qassim and his companions, beginning the search even before their exoneration. The U.S. was wary of sending them to China. Beijing severely punishes Muslims from the far west who criticize the Communist government or advocate independence. Unwilling to let the men live in the U.S., American officials say they approached more than 100 countries. All said no or waffled, fearful of upsetting China and reluctant to take on America’s problem. Then Albania, an impoverished land with a large Muslim populace and a brutal communist past, said yes in April.

Messy Struggle

The decision pushed the country of some 3.5 million into a messy big-power struggle. Soon after the five Uighurs reached Tirana, China accused Washington of hypocrisy for letting them go. Beijing demanded that Albania hand over the men, whom it calls terror suspects. Prime Minister Sali Berisha says he was harangued by China’s ambassador. Mr. Berisha says he’s glad he gave the five Uighurs a haven, but regrets that it “has become very noisy around here.” The Chinese Embassy in Tirana declined to comment. Guantanamo Bay now holds around 460 detainees. These include four who have been declared “no longer enemy combatants” -- bureaucratic jargon for innocent. About 116 others, though not exonerated, are no longer considered a serious threat or valuable to U.S. intelligence. Among those who have been cleared but remain at Guantanamo is Zakirjan Hassam, an Uzbek dissident desperate to avoid going back to Uzbekistan. Like China, Uzbekistan rallied early to the “war on terror,” viewing it as a vindication of its own harsh measures against restive Muslims. Before sending detainees home, U.S. officials seek guarantees they will be treated humanely and prevented from causing trouble for America in the future. Those issues have slowed U.S. negotiations with Saudi Arabia over the repatriation of Saudi nationals at Guantanamo, although 15 Saudis there were sent home last month. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has cited such complications in explaining why the Guantanamo prison can’t simply be closed. The U.S. is working “almost daily” with foreign governments to reduce the number of prisoners, she has said. On a visit to Britain in April, Ms. Rice said: “We don’t want to be the world’s jailer.” Guantanamo critics blame the dilemma on the Bush administration’s refusal to adopt swift and transparent procedures for judging guilt or innocence. They say lengthy incarceration leaves people with the stigma of terrorism even if they eventually get cleared. Lawyers for Mr. Qassim and other absolved detainees say those who are found innocent should be allowed to settle in America. “The U.S. made this mistake,” says Sabin Willett, a Boston corporate lawyer who early last year volunteered to defend Mr. Qassim and another Uighur detainee. “After four years at the Guantanamo prison, America owes them better than to be swept under an Albanian rug.” Unlike many of the world’s Muslims, China’s Uighurs often like America. Chafing at rule by Beijing and a flood of ethnic Chinese into their region, many Uighurs look to the U.S. for help. Calls for outright independence from China have faded but anger at police heavy-handedness and restrictions on religious worship have triggered sporadic bouts of unrest. Mr. Qassim says that before leaving China in 2000 he used to listen to U.S.-funded Radio Free Asia, which broadcasts news in Uighur and other Asian languages. “It was very sad and disappointing to have a country we respect treat us in the way we’ve been treated,” he says. A native of Yining, a town near China’s border with Kazakhstan, he used to work in a state leather factory and as a small-time trader. He ran into trouble after anti-Chinese riots in his hometown in 1997. Mr. Qassim says he didn’t take part in the turmoil, which left at least nine dead, but he began to speak out against Chinese rule. Mr. Qassim says he also grew more interested in Islam, and was jailed for seven months on suspicion of anti-Chinese activities. In 2000 he moved to neighboring Kyrgyzstan, hustling for work in a big bazaar. There he met a fellow Uighur from Yining, Adel Abdu Al-Hakim, now with him in Albania. The two later decided to move to Turkey, hoping to work at a leather-jacket factory run by a ethnic Uighur living there. With no money for air tickets, they headed overland for Pakistan, where they say they intended to get visas for Iran. Discovering this would take months -- and fearful of staying on in Chinese ally Pakistan -- they opted to wait in Afghanistan. The two men say they left Pakistan in the summer of 2001 to join some 30 anti-Chinese Uighurs living near the Afghan city of Jalalabad. The U.S. would subsequently describe their settlement as a “training camp.” The Uighurs in Guantanamo strongly denied that description in their tribunals. According to transcripts, each insisted the place was just a cluster of ramshackle buildings. Mr. Qassim says he studied the Quran and occasionally took pot shots with a Kalashnikov rifle, but received no “terrorist” training. Both he and Mr. Abdu Al-Hakim say they had never heard of the Afghan-based Osama bin Laden and had no intention of joining him. After the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Mr. Abdu Al-Hakim heard reports of a likely U.S. attack on Afghanistan from a Uighur who listened to Radio Free Asia. He says he didn’t expect any trouble, as the Uighurs had no quarrel with America. Late at night a few days later, U.S. planes bombed their settlement. Ayup Hajimemet, now 23 and the youngest of the five Uighurs in Albania, says he arrived at the village just as the bombing started. He joined a group of fleeing residents, including Mr. Qassim, and headed for the mountains. They later discovered their destination was called Tora Bora, the focus of a failed U.S. hunt for Mr. bin Laden. Hungry and frightened, they say they sought shelter in a cave, only to be driven out by wild monkeys throwing stones. “We don’t fit in anywhere in the world. Even monkeys don’t want us,” says Mr. Qassim.

Betrayed by Locals

After some two months of foraging and begging for food, Mr. Qassim and other Uighurs decided to get out of Afghanistan. They made a three-day trek across snow-covered peaks into Pakistan. Upon arriving, they say, local tribesmen gave them a warm welcome -- and then betrayed them. After a lamb feast, the 18 Uighurs were taken to a mosque, herded into vehicles, driven to a jail and handed over to U.S. forces, who flew them to an American prison in Afghanistan. Mr. Abdu Al-Hakim says the 18 were captured by Pakistani bounty hunters. He overheard people saying the hunters received $5,000 each for the captives from the U.S. A Pentagon spokesman said he couldn’t discuss “tactics, techniques and procedures” used to combat terrorism. After some six months of interrogation in Afghanistan, the 18 Uighurs captured in Pakistan were put on a plane to Guantanamo, their heads hooded, their arms and legs tethered. Upon arrival in Cuba, they say they were each given an orange jumpsuit, a copy of the Quran and an “internment serial number.” Mr. Qassim became ISN #283. China cheered the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, linking it to its own crackdown in Xinjiang. Beijing soon issued a report claiming the Uighur activists were “supported and directed by Osama bin Laden.” It named as an al Qaeda affiliate a small Uighur group called the East Turkistan Islamic Movement. At Guantanamo, much of the interrogation of the Uighurs focused on the movement, which the U.S. in late 2002 declared a terrorist organization. The Uighurs in Guantanamo denied any involvement with the group. The U.S. let Chinese interrogators interview Mr. Qassim and other Chinese nationals at Guantanamo, according to the men and court documents. Most refused to talk, but they were rattled: Mr. Qassim says the Chinese made veiled threats against their families back in Xinjiang and appeared to have had access to information the Uighurs had given U.S. interrogators. A Pentagon spokesman said the U.S. “works with a variety of nations to try and determine the status of detainees.” Out of 22 Uighurs with Chinese nationality sent to Guantanamo, U.S. officials concluded early on that Mr. Qassim and the four now with him in Albania weren’t terrorists. But for reasons that remain unclear, U.S. authorities failed to inform the five Uighurs of that. In early 2004, the Pentagon asked the State Department to start looking for a possible home for them abroad. Later that year, the Uighurs and hundreds of others got their first chance to formally contest their status as “enemy combatants.” This followed a 2004 Supreme Court decision that prompted the Pentagon to set up so-called Combatant Status Review Tribunals. Detainees appeared before the secret panels shackled and without lawyers, but were allowed to defend themselves. Remarks in declassified transcripts suggest the Uighurs’ hearings took place in late 2004. “Treating a person like me this way is not fair,” Mr. Qassim told the tribunal, claiming that he opposed China, not America. The U.S., he complained, “was to help young Uighur people, and now they are saying we are the enemy.... We Uighurs have more than one billion enemies and that is enough for us.” Mr. Hajimemet, the young man who reached Afghanistan just as bombs were falling, was the only one of the five Uighurs to learn much English. While in prison, he says, he sometimes lashed out in response to taunts from American guards and to the daily humiliations of “being treated like an animal.” He spat at a guard. “Even a donkey kicks back,” he says. He wasn’t tortured, he says, but on one occasion was thrown against a metal bed, leaving him with a lingering back injury. The review tribunals set up in 2004 examined 558 cases in all and ruled that 38 detainees should be reclassified as “no longer enemy combatants.” Among them were the five Uighurs now in Albania. The 13 other Uighurs who had been seized with them in Pakistan are all still “enemy combatants” and remain in Guantanamo. In March 2005, Mr. Willett, the Boston lawyer, filed a petition in the U.S. to force the government to bring Mr. Qassim and Mr. Abdu Al-Hakim to court. U.S. officials declined to inform him that his clients already had been cleared. “The whole approach has been to keep Guantanamo a great big secret,” says Mr. Willett, a partner at Bingham McCutchen LLP. “In the fog of war, mistakes are made,” he adds. “The dishonor comes of hiding them.” Four months later, in July, Mr. Willett got permission to visit Mr. Qassim and Mr. Abdu Al-Hakim in Cuba. The two men were chained to the floor in a tiny plywood hut, the lawyer says. Only at this meeting was he finally told they had been exonerated. Mr. Willett returned to the U.S. and filed an emergency motion demanding their immediate release. About a month later, Mr. Qassim and the other exonerated Uighurs were moved to less-severe quarters in nearby Camp Iguana. They could walk around without chains and were allowed to watch nature videos. News broadcasts were banned. Mr. Willett requested permission to send a Uighur-English dictionary and other language materials but was told this was forbidden. Defense Department rules bar inmates from developing any skill, even English, that might be used against the U.S. At a U.S. court hearing last August on Mr. Willett’s call for the prisoners’ release, a federal judge denounced the term “no longer enemy combatant” as “Kafkaesque.” When assured by a government lawyer that the case would be resolved “soon,” the judge snapped, “Define soon.” In a December ruling, he declared the continued detention of Mr. Qassim and Mr. Abdu Al-Hakim was “unlawful” but said he couldn’t order the release of the innocent men because this would involve immigration issues outside of his purview. Mr. Willett appealed, and a hearing was set for May 8. With the legal pressure mounting, the government stepped up previously fruitless efforts to find the Uighurs a home. U.S. officials at one time considered letting the Uighurs into America, but that option was rejected “at a senior policy level” out of concerns over possible litigation and security, says a senior State Department official. Sending the Uighurs back to China was never an option, say U.S. officials. The State Department’s annual report on global human rights, released in March, concluded that China had “used counter-terrorism as an excuse for religious repression of Uighur Muslims.” It also reported that a Uighur sent back to China from Nepal against his will had been executed. The State Department’s latest report on global terrorism, issued in April, now lists the East Turkistan Islamic Movement as a group of “concern.” Albania was first approached about taking the Uighurs late last year, and initially balked. In April, the U.S. ambassador to Tirana went to see Prime Minister Berisha. Mr. Berisha had assisted the U.S. in the 1990s, helping the Central Intelligence Agency hunt down alleged Islamic militants in Albania. The militants were later expelled to Egypt and, in two cases, hanged. Albania was also seeking U.S. backing to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Mr. Berisha says he told the ambassador that Albania would take the Uighurs as a “favor to a friend,” so long as America was sure they weren’t terrorists. The U.S. agreed to cover the costs of their resettlement. Albania, he says, owes a lot to America, most recently for its 1999 military intervention in Kosovo, populated largely by ethnic Albanians. China, which under Mao Zedong was a close ally of Albania, heard of the plan and was livid. A scheduled visit in May to Beijing by Albania’s foreign minister was called off. Three days before the May 8 U.S. court hearing on the Uighurs, Mr. Qassim and the four others were bundled onto the transport plane. Though told they were going to Albania, they were terrified the flight might end in China. Mr. Qassim says he calmed down only when the door of the plane opened and he saw European faces.

‘Pay Any Price’

Local newspapers splashed their arrival across the front pages. The opposition blasted the government for upsetting China. Two days after the Uighurs landed, Prime Minister Berisha met with Vice President Dick Cheney in Croatia at a gathering of three countries hoping to join NATO. The prime minister said Albania was ready to “pay any price” to join the alliance. Mr. Cheney said he endorsed the entry of Albania, Croatia and Macedonia. In Tirana last week, Mr. Berisha said he was baffled that so many major nations declined to take the Uighurs, including the U.S. itself and the European countries that call for Guantanamo’s closure. “Big countries don’t like to deal with small problems,” he said. Mr. Qassim and his companions, meanwhile, have shaved off the long beards they had grown in jail to fit in with zealously devout Arab inmates. They now have a driver to take them around Tirana, and have found a Turkish restaurant where Turkish-speaking waiters can just about make out their orders. China’s official news agency, Xinhua, says the five men are “faring poorer than rats crossing the street.” On a visit last week to an Internet cafe, the five men searched for news about their case in their native tongue. Then they watched footage from the 9/11 attacks in New York. They’d never seen the images of hijacked planes flying into the World Trade Center before, and they wanted to know what got America so angry. Mr. Qassim groaned as he saw the jets slam into the towers. “This is awful, really awful,” he said. “If this hadn’t happened, we would never have gone to Guantanamo.”